In looking for freedom we found slavery

In 2013 the artist Grayson Perry delivered a series of BBC Reith Lectures entitled ‘Playing to the Gallery’. The series of four talks gave an amusing and enlightening view of the art world.

The first lecture, called ‘Democracy has Bad Taste’, discussed the work conducted between 1994 and 1997 by two Russian artists, Komar and Melamid, called the “People’s Choice” series. This work was the result of a study from 11 countries, including the USA, Russia, China and France, to understand what they wanted to see in art. The purpose was partially a political statement to reveal democracy as a flawed concept as non-experts select leaders and partially an artistic statement to prove that the general public is an acceptable judge of art. This was a controversial position to take against the art world but the argument attempted to echo the trust that countries such as the USA place in the public in electing a president.

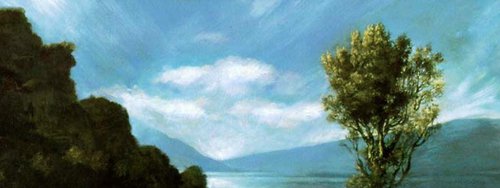

In what might be considered as the ultimate irony, Komar stated that he wasn’t so concerned that people enjoyed the work as long as it provoked thoughts of free will versus predetermination. In searching for a new freedom the artists discovered that the people surveyed essentially all wanted the same thing - blue landscapes. Writing about the experiment later, they conclude that:

In looking for freedom, we found slavery.

This begs the question is there always a right way and wrong way to do something?

Clearly there is in certain situations: for health and safety, security and possibly etiquette reasons, for example. But as the artistic example above shows, there are situations where conforming to a predetermined expectation isn’t necessarily beneficial.

Understanding our own points of differentiation can be extremely useful when it comes to our development. A good starting point can be found by dividing ourselves into personality type A or B. Occasionally controversial, this approach has valid benefits in the world of commerce. Understanding where you fit on the scale can play an important role in focussing on where personal development training will be best suited.

So where does freedom lie and what does freedom look like? In order to answer that, we need to think about a difficult question. Is there a possibility that people may not actually want freedom? For many people, and in particular, people in the role of learners, it is more important to have strong direction and to some extent to be spoon fed. We are conditioned from a very young age to fit into a system that operates on a linear model of progression, despite the fact that this one-size-fits-all approach is somewhat unrepresentative of the rest of society. This conditioning can be exploited, as newspaper editors have known for centuries: often filled with provocative positions and moral judgements, readers enjoy the opportunity to regurgitate thoughts and views as if they are concrete facts.

The world has been divided on this issue since the days of Socrates, as Martin Robinson demonstrates entertainingly in his recent book Trivium 21c. At one extreme are the grammarians – prescriptivists who believe strongly in education as the consumption of facts. At the other are the progressives, who are considerably more laissez faire and think education should be closer to self-exploration and self-expression.

And whilst there are many people who simply want to be told what to do, how to do it and when, there are also many people who are free thinkers. In reality there are very few people who are at the extremes of these positions and most fall somewhere along the spectrum. It is the group that tend towards the free thinking end of the scale that we aim to appeal to. Our approach to this group is to provide tools that allow for open and social learning.

Sir Ken Robinson is an educationalist with refreshingly clear views. If you don’t know about him then you may be interested to hear him on BBC’s Desert Island Discs. His TED Talk (shown below) - How Schools Kill Creativity - gives an amusing and powerful case for changing our thinking around education. Of particular note in the context of our title is the profoundly sensible concept that we should shift from a manufacturing model where output of a ‘product’ is the goal, to an agricultural model where organic growth is achieved. This means moving educators from a position of line manager to something more akin to that of a farmer, in the way that they create the environment for growth.